Divers, have you entered the Randall Zone?

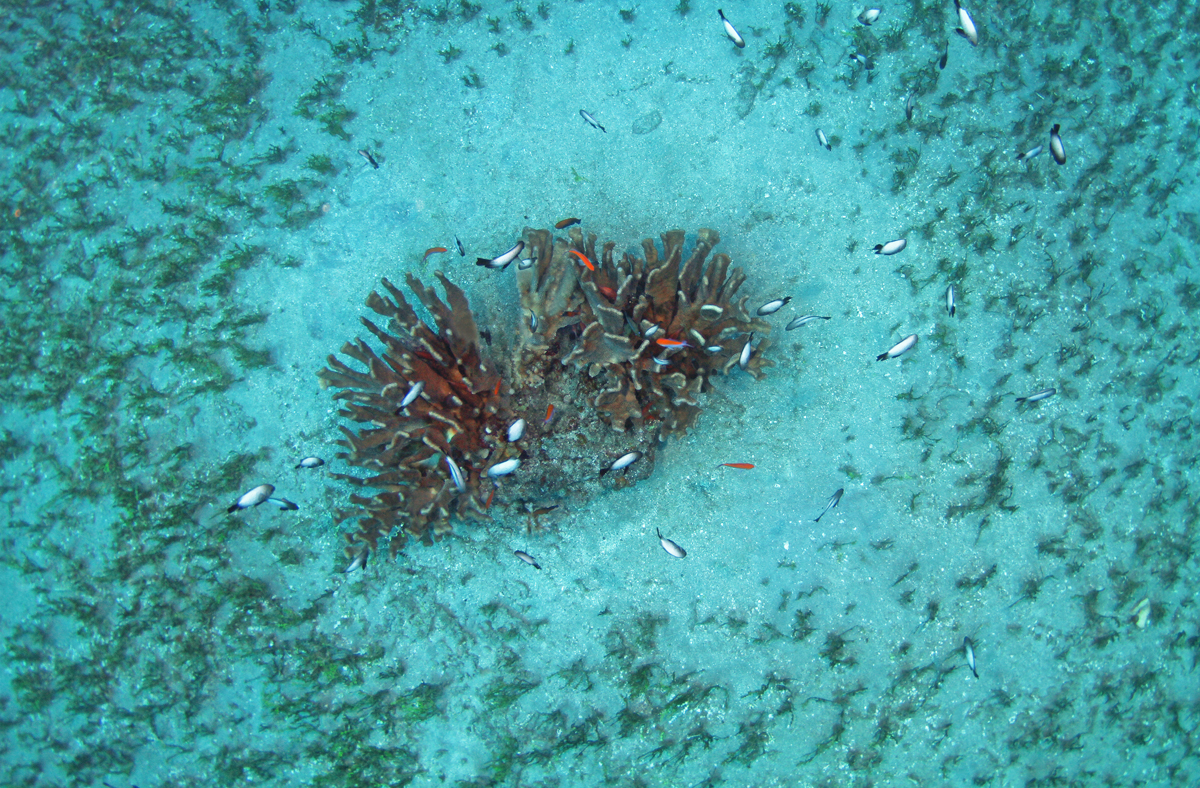

You might have without even knowing it. A Randall Zone is an area around – or next to – a reef or object where no sea grass or algae is growing. It can be around a small antler coral colony as pictured below, or it can be around a large object such as a shipwreck. Small objects have small Randall Zones and large objects, larger ones.

Most divers do not even notice these zones, particularly the smaller clearings. But a renowned Hawai‘i fish scientist took notice of these areas exactly 60 years ago when he was just beginning his career. Here’s how he figured out why these bare areas existed.

A Randall Zone (clearing) around an antler coral (Pocillopora eydouxi) off of Maui, Hawaii. A calcareous alga called Halimeda surrounds the clearing. Photo: P. Fiene.

In 1959 a young fish scientist named John E. “Jack” Randall began directing a marine biological survey of the newly-created Virgin Islands National Park on St. John island. Aerial USGS photographs of the coastline were used to chart the marine habitats. Because the water was so clear, Jack and his fellow researchers noticed a striking feature. There was a band of bare sand between the fringing coral reef and the sea grass beds farther offshore.

Aerial view of Lameshur Bay, St. John, Virgin Islands. A band of sand is visible between the fringing reef next to the island and the sea grass beds offshore. Image from Google Earth 2/12/2013.

At first they thought the band was due to the slope, or maybe coarseness or shifting of the sand. They dispelled those hypotheses, however, with sand sampling and further surveying. Next they thought the band might be the result of grazing by reef fish. Perhaps the fish would only venture so far from the shelter of the reef to feed. To test this hypothesis they dug up and transplanted 2 square feet of sea grasses into the bare area. By the time they returned to transplant the second shovelful, parrotfish were already eating the first. Within 24 hours they had consumed almost all of it.

In another experiment they connected the fringing coral reef to the algae with a 1-foot wide strip of seagrass – a distance of 20 feet. Within 2 days the seagrass was eaten 5 feet away from the reef. In 10 more days the sea grass was eaten 7 feet away. And 6 weeks after initial transplanting, all of the seagrass had been eaten right out to the already existing edge.

Are you wondering, “How in the world do the fish know how far they can safely go away from the reef?” Well, of course they are not “doing the math.” But at least in the case of the circular clearing around an object, it might indeed result from basic geometry.

That fixed object has a limited number of shelter spaces, and therefore a limited number of fish can live there. So let’s assume that all the shelter spots are taken and there is a relatively stable number of fish living on/in/around that object, a percentage of which are grazers such as surgeonfish and parrotfish. Like any animal, these fish are not going to waste energy; they are going to eat the algae nearest their shelter first. Once that is consumed they are forced to graze a little farther out, then a little farther. As they move away from the object, the perimeter of the grazing area increases. At some point the amount of daily growth occurring in the algae at the perimeter will be greater than the amount those fish eat in one day. That determines the width of the Randall Zone around that particular object.

In the case of a linear Randall Zone next to a reef, the geometry of an expanding perimeter around a central object wouldn’t apply. But, other factors such as instinctive predator avoidance may limit the distance fish travel away from their refuges. Also at play would be the species and number of grazing fish (and other grazers such as sea urchins), their interactions with each other, and the species and number of predators. Environmental conditions would also influence the species and growth rates of the algae. It’s interesting to think about all the factors that result in the fish going just that far – and not ONE inch farther.

Olowalu, Maui coastline showing the bright blue Randall Zone just offshore.

Here in Hawai‘i we have very little sea grass, but we still see this phenomenon associated with a type of calcareous algae called Halimeda. To the right is a Google Earth image of a section of reef off of Olowalu, Maui. The macro-algae that is growing on the offshore side of the band of sand in this photo is Halimeda. Other places around Maui that we see Randall Zones are around WWII wrecks, artificial reefs and natural patch reefs.

And just because these areas are void of algae and appear bare, they are a habitat in themselves. Mantis shrimps, snails, slugs, octopuses, fish that can make their own shelters in open sand such as tilefish, gobies and perch – all these and many more can permanently reside in the Randall Zone, even though grazing fish must retreat to the shelter.

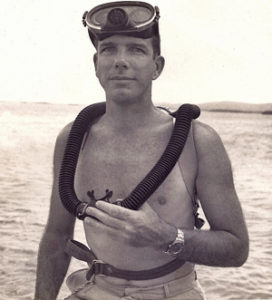

Jack and his fellow researchers figured out this grazing phenomenon almost 60 years ago near the beginning of what would become a remarkable career as Senior Ichthyologist at the Bishop Museum in Honolulu. During this time he has discovered and named more than 800 valid coral reef fish species – more than anyone else in history has (or ever will!) And he is still describing new fish species and authoring and co-authoring papers and books. His long-awaited memoir is to be published sometime this year.

Dr. John E. “Jack” Randall, 1963

When we enter the Randall Zone we are entering an area named for a giant in the field of coral reef fish systematics and biogeography. And when we exit the Randall Zone many of the reef fish that we see every day have been described by Jack. The Randall Zone name is just one of many ways he has been honored for his lifetime contributions to the knowledge of coral reef fishes. And it’s even more special for Hawai‘i divers because Jack Randall chose Hawai‘i to live and pursue his passion. Here he has learned, shared his knowledge, and mentored others in the field of coral reef fishes for decades – and continues to do so into his 90s.

Written by Pauline Fiene

Thanks to Cory Pittman for hypotheses on factors determining Randall Zone size, and thanks to Dr. Richard Pyle for Jack’s most recent valid species count.

*****************

Comments 6

That’s very cool!

This brought tears to my eyes Pauline! I remember meeting Jack so many years ago while I was Captain for Mike Severns Diving. We always used his book as the Bible to fish identification. He made quite the impression on me back then and I’m so happy to hear he is still living his dream. His knowledge and passion will remain long into the future! We love you Jack!

Pauline, you were the first to point out the Randall zone and I was fascinated. I had “seen” it many times without understanding why the zone was so specific to an area. Sure makes diving a better adventure when we have great teachers to explain the wonders of the ocean.

Did his book come out? Would love to buy a copy and read it.

Author

Hi Judy. The book is in the publisher’s hands. He doesn’t know the publication date yet. I will let you know.

Is there any chance I could get access to the date of this photo showing the mangrove region just north of G. Lameshur Bay? I am actually trying to analyze the impacts of hurricanes on this mangrove

Author

Hi Paul. Yes, it is a Google Earth image from 2/12/2013. I will add the photo credit now. Thanks! And good luck with your project.